Theological Notes of the Catholic Church

Theological Notes and Their Application to Contemporary Catholicism

I was recently challenged, through conversation with Jay Dyer (Eastern Orthodox former Catholic), about the nuances of Denzinger, Ott, and the relation of the believer to “what is dogma”.

Something that came of it was understanding the theological notes of the Catholic church (a collection), that which differentiate between what is “dogma” required belief, and theologically acceptable belief.

A crucial motto for Catholics navigating theological discourse today is the phrase: In necessariis unitas, in dubiis libertas, in omnibus caritas—"In essentials, unity; in doubtful matters, freedom; in all things, charity." This principle, often attributed to St. Augustine but more accurately linked to Lutheran theologian Rupertus Meldenius, underscores the importance of distinguishing between non-negotiable doctrinal truths and those theological opinions open to legitimate discussion. In times of crisis, Catholics must carefully apply this maxim to avoid both heretical deviation and schismatic rigidity.

However, what constitutes "essentials" (necessaria) and "doubtful matters" (dubia) is not always immediately clear. The Catholic Church provides a structured hierarchy of doctrinal certainty known as the Theological Notes, which categorizes teachings based on their degree of authority, certainty, and required assent. These Notes provide a framework for theological fidelity and permissible inquiry.

The Hierarchy of Theological Notes

The theological grades of certainty are as follows, with increasing levels of binding authority:

De Fide (of the faith)

These truths are explicitly revealed in Sacred Scripture or Sacred Tradition and have been definitively declared by the highest Church authority (e.g., an ecumenical council or ex cathedra papal decree).

Example: The doctrine of the Beatific Vision (Council of Florence, 1439) and the dogma that souls who die in mortal sin are eternally damned (Lateran IV, 1215).

Denial: Constitutes formal heresy (haeresis), resulting in automatic excommunication (latae sententiae).

De Fide Ecclesiastica (of ecclesiastical faith)

These doctrines are explicitly defined by Church authority but are implicitly contained in divine revelation.

Example: The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Pius XII, Munificentissimus Deus, 1950).

Denial: Constitutes heresy and is equally grave as de fide denial.

Sententia Fidei Proxima (proximate to the faith)

Example: That Mary remained a virgin in partu (during childbirth), meaning she miraculously gave birth without violating her physical integrity.

This belief is not explicitly defined as dogma, but it has been universally upheld by the Church Fathers, the Scholastics, and theologians as a truth derived from divine revelation.

It was affirmed by early Church councils (e.g., Lateran Synod of 649 under Pope St. Martin I) and by popes (e.g., Pope Pius XII in Mystici Corporis (1943)), but it has not been dogmatically defined in the same way as the perpetual virginity itself (which is de fide).

It remains Sententia Fidei Proxima because to deny it is to undermine the traditional understanding of Mary’s virginity and, by extension, Christology.

Denial: Constitutes error proximate to heresy (errori proxima haeresi). While not de fide, rejection of this doctrine strongly contradicts the unanimous tradition of the Church.

Sententia Certa (theologically certain)

These teachings are derived from theological reasoning and the consensus of the Magisterium but have not been explicitly defined as dogma.

Example: The primary purpose of marriage is procreation, with secondary purposes being mutual support and regulation of concupiscence (Casti Connubii, Pius XI, 1930).

Denial: Constitutes error in fide (error against faith).

Sententia Communis (common teaching)

These are widely accepted theological opinions that, while well-supported, have not reached the level of dogmatic definition.

Example: The assertion that all deliberate violations of the Sixth Commandment (non moechaberis) are grave matter.

Denial: While not heretical, such denial would constitute theological temerity (temeritas), which is sinful without reasonable theological argument.

Sententia Probabilis (probable opinion)

These are well-reasoned theological conclusions, but they lack universal agreement or definitive authority.

Example: Whether Judas Iscariot received the Holy Eucharist at the Last Supper (debated among theologians such as St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Augustine).

Denial: Permissible, provided it is done with due reverence to theological authority.

Thus, Catholic fidelity demands strict adherence to De Fide and De Fide Ecclesiastica teachings, while allowing for limited theological discourse on Sententia Certa and Sententia Communis—provided the principles of theological piety and prudence are observed. Sententia Probabilis, however, remains fully open to debate.

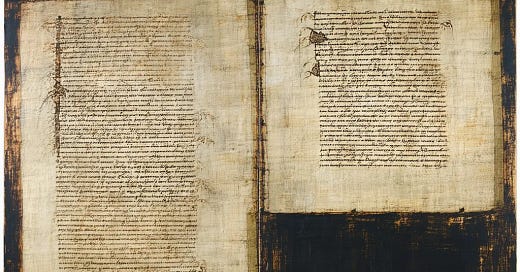

Theological Notes were not formally issued by the Vatican as an official magisterial document. Instead, they were developed over time by Catholic theologians as a systematic way to classify doctrinal teachings based on their level of certainty and the degree of assent required.

The most famous articulation of the Theological Notes comes from Ludwig Ott in Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (1954), but the framework itself has roots in Scholastic theology, particularly in the works of Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) and other post-Tridentine theologians.

Where Did They Come From?

Scholastic Theology – Medieval and post-medieval theologians, especially St. Thomas Aquinas, Suárez, and Melchior Cano (1509–1560), developed the idea that different levels of theological certainty exist.

Neo-Scholasticism – The classification became more refined in the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in manuals of dogmatic theology.

Ludwig Ott’s Systematization – His Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma (1954) became the most widely referenced presentation of these categories, even though the underlying distinctions had existed for centuries.

Is This Magisterial?

The Vatican has never dogmatically defined or issued an official document listing these categories. However, the concept is widely accepted in theological education and referenced in Catholic seminaries, particularly in pre-Vatican II theological manuals.

Some magisterial documents reference different levels of theological certainty, even if they do not use Ott’s exact terminology. For example:

Vatican I (1870) affirmed that some doctrines must be held de fide (dogmatically).

Pope Pius XII’s Humani Generis (1950) acknowledged different levels of theological authority in magisterial teachings.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (1998) under Cardinal Ratzinger outlined different levels of theological teachings in Doctrinal Commentary on Ad Tuendam Fidem.

Theological Notes vs. Magisterial Teachings

The Theological Notes are a theological framework—not an infallible magisterial decree.

However, they are widely used and accepted by Catholic theologians to help assess the binding nature of different teachings.